“Its unique power was a “matter making images seen.”[1]

- Cinema followed a pattern of enthusiasm for its medium and possibilities. à Emphasis placed on potential and the future.

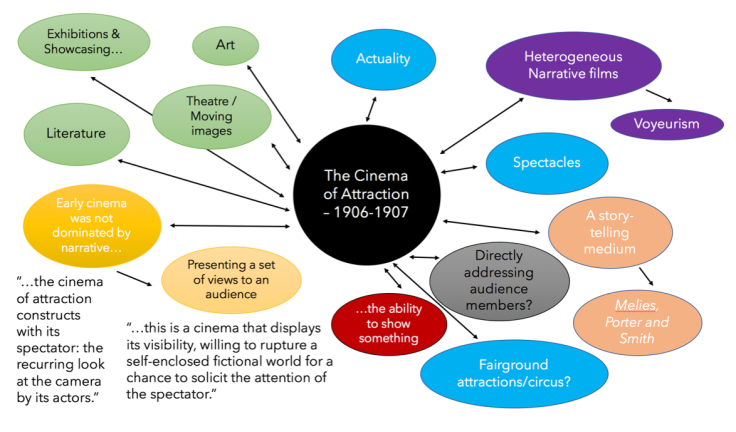

- Cinema and film are traditionally regarded as a narrative based medium of story-telling (Narrative construction and editing.)

- Early cinema was not dominated by narrative, it evolved and developed overtime; emphasis was originally placed on actuality the attraction.[2]

“In other words, I believe that the relation to the spectator set up by the films of both Lumiere and Melies (and many other filmmakers before 1906) had a common basis, and one that differs from the primary spectator relations set up by narrative film after 1906.”

“In fact the cinema of attraction does not disappear with the dominance of narrative, but rather goes underground, both into certain avant-garde practices and as a component of narrative films, more evident in some genres (e.g., the musical) than in others.”

- Cinema is based on quality and its ability to demonstrate and show something. This is contrasted on narrative cinema which often enters realms of voyeurism. (Exhibitionist cinema)

“the cinema of attractions construct with its spectator: the recurring look at the camera by actors. This action which is later perceived as spoiling the realistic illusion of the cinema, is here undertaken with brio, establishing contact with the audience.”

“…perhaps the dominant non-actuality film genre before 1906, is itself a series of displays, of magical attractions, rather than primitive sketch of narrative continuity.” à “The story simply provides a frame upon which to string a demonstration of the magical possibilities of the cinema.” :65

[1] Femand Leger, “A Critical Essay of the Plastic Qualities of Abe Gance’s Film The Wheel” in Functions of a Painting, ed, and intro. Edward and Fry, trans. Alexandra-Anderson (New York: Viking Press, 1973), 21.

[2] Robert C. Allen, Vaudeville and Film: 1895-1915, A Study in Media Interaction (New York: Arno Press, 1980), !59-212-213.

“The relation between the film and the emergence of the great amusement parks, such as Coney Island, at the turn of the century provides rich ground for rethinking the roots of early cinema.” :65

- Expression and demonstration of magic and trickery were a fundamental element of early cinema. attraction was used as a tool to immerse the viewer within the films. à Close-ups and enlargement was used as a technique of attraction rather than a conveyor of the narrative.

“The enlargement is not a device expressive of narrative tension; it is in itself an attraction and point of the film.” [See Footnote 8 of original text]

“An attraction aggressively subjected the spectator to “sensual or psychological impact.” According to Eisenstein, theatre should consist of a montage of such attractions, creating a relation to the spectator entirely different from his absorption in “Illusory imitativeness.” [1]

“Then as now, the “attraction” was a term of the fairground, and for Eisenstein and his friend Yuketvich it primarily represented their favourite fairground attraction, the roller coaster, or as it was known then in Russia, the American Mountains.” [2]

“…offering a new sort of stimulus for an audience not acculturated to the traditional arts.” :66

- The entertainment industry evolved and developed growing to accept middle-class cultures à Linked to discourses of liberation and freedom.

“…its freedom from the creation of a diegesis, its accent on direct stimulation.” :66

“…its creation of the new spectator at the variety theatre feels directly addressed by the spectacle and joins in, singing along, heckling the comedians.” :66

- Cinematic format morphed and changed to incorporate more variety by combining traditional and modern techniques and genres.

“…trick films sandwiched in with farces, actualities, “illustrated songs”, and, quite frequently, cheap vaudeville acts. It was precisely this non-narrative variety that placed this form of entertainment under attack by reform groups in the early teens.” :67

- There was substantial concentration on artificial stimulation that was often featured in popular culture and arts to…

“…inject into the theatre, organising popular energy fo radical purpose.” :67

“The period from 1907 to about 1913 represents the true narrativization of the cinema, culminating in the appearance of feature films which radically revised the variety format.”:67

- The camera became a device for magic and trickery, an expression of playful and cinematic attraction in an attempt the engage and stimulate viewers that altered traditional ideology surrounding audience theory reflecting viewers as passive and unquestioning viewers to a more participatory standpoint.

- Causality + Linearity = Narrative [Linked to basic continuity editing] à The spectacle unfolds and builds tension amongst audience members

- Slapstick…

“Did a balancing act between the pure spectacle of gag and the development of narrative.”[3] :67

[1] Eisenstien, “Montage of Attractions,” trans. Daniel Gerould, in The Drama Review, 18, 1, (March 1974), 78-79.

[2] Yon Bama, Eisenstein (Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Press, 1973), 59.

[3] Paper delivered at the FIAF Conference on Slapstick, May 1985, New York City.

HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENTS & ARCHEOLOGIES

- Camera Obscura, Views, Sights, Exotic/Unfamiliar, ‘Phantasmagoria’, Peepshow

Melies – Illusionist (Conjurer)

- Early cinema was ‘exhibitionist’, not narrative based; reflective of a different set of perceptions that related to cinematic mechanisms and experiential qualities that we now take for granted or overlook [Based on trickery, effects etc]

- Making images seen, emphasising visuality and perception – ‘harnessing visibility’ [‘Attractions’ similar to that of a fairground or circus]

- I feel that now, we expect this as a matter of quality, unlike in the past, we are very much aware of the processes and ‘tricks’ that go into cinematic media, is this linked with our increasing involvements with producing and distributing our own media and technological accessibility or the ‘Prosumer’?

Thomas Edison 1894 – Boxing Cats

- Exploring (then) technological ‘Wonders’ – exploration of a medium’s possibilities or affordances

- Exploring the experiential shifts from previous technologies and cultural forms [Shocks] -> 3D, IMAX Cinema etc.

- Dioramas & Tableaux… -> Daguerre type photography, [Interlinkages between film, art and painting with light, theatre; all used to create immersive and 3D appearance] -> Manipulated to simulate the changing seasons.

- Panoramas… 360-degree medium patented by British artist Robert Barker in 1787

- Immersive Installations that transported people into the very space they were viewing (E.g. The Rotunda Leicester Square)

- Panoramic Forms & The Everyday… focusing on the ‘every day as a valid object of representational attention’, focusing on the every day as a form of scientific enquiry [New attention to detail, accessing information about movement that would be impossible to witness with just the human eye alone].

- The Panoramic Entails… Vignettes, scenes, views, fragments: ‘An Objective overview of phenomena constituting the everyday experience’, Habits, Manners, Descriptive of newly observable, detail, the wandering gaze.

Phantasmagoria & Everyday Urbanism:

- Singer, Ben (1995) ‘Modernity, Hyperstimulus, and the Rise of Popular Sensationalism’ in Leo Charney and Vanessa R. Schwartz (eds.) Cinema and the Invention of Modern Life, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University Press.

- Modernity, trains, industrialisation, Speed, Shock, Hyperstimulus, Sensationalism.

- Modern life was cinematic before the event

- Distributed across urban spaces and consuming cultures (e.g. The Whirlwind of Death 1905)

- Surely there are connections that still exist today? Why do we have such a fascination with horror, gore and death?

Attention, Perception and Mechanical Reproduction:

- Modern Visuality involved a new kind of perceptual competence

- The ‘frenzy of the visible’: impressions and stimuli

- Everyday life in animated form –> Liveness and Illusion

- An interest in the dynamics and physics of movement, speed etc.

- Thomas Edison, The Electrocution of an Elephant… Scientific inquiry, movement revealed through technology, recording the moment, popular entertainment (Coney Island)

‘Exhibitionary Complexes’:

- Shared trajectories and traits between cinema, zoo and the department store…

- New, shared and connected methods of display, attraction and exhibition such as display cases, simulated spaces and dioramas

- Attention directed through a staged exhibit

- Cultural Capital, value formation and self-regulating citizens, Navigating knowledge and meaning

‘Screening’ & Multi Media Immersion and Interactive Participation:

- The combination of different media forms in an attempt to physically immerse audience members within artificial spaces in a manner that invites active involvement within their surroundings.

- Digital, interactive & Mobile media: Exploring the embodied, visceral engagement with technology

- How does this organise our movement and our time

- An active encounter with technology that generates unpredictable effects

References:

Swanson, G. (2017) The “Cinema of Attractions”, Visceral Exhibitionism and the (Social) Science of the Everyday (GS). Media Culture 2 [Online] Available from: https://my.uwe.ac.uk. [Accessed 23 January 2017]

Rose, M. (2017) Media Futures. Media Culture 2 [Online] Available from: https://my.uwe.ac.uk. [Accessed 23 January 2017]

Gunning, T. (1986) ‘The Cinema of Attractions: Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant-Garde’, Wide Angle, Volume 8. Nos 3 & 4.

Swanson, G.; Agusita, E. (2016-2017) Media Culture 2: Creative Cultural Research Module Reader. Bristol: Forest Carbon

González, R. (2006) George Melies – The Conjuror 1899. YouTube [Video] 6th May. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zs5BBaNJ6mg&feature=youtu.be [Accessed 23 January 2017]

LibraryOfCongress (2009) The Boxing Cats (Prof. Welton’s). YouTube [Video] 26th March. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6qre61opE_g&feature=youtu.be [Accessed 23 January 2017]

HuntleyFilmArchives (2013) E. J. Marey in 1891. Film 17436. YouTube [Video] 30th September. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8aU1RXkJZ_Y&feature=youtu.be [Accesed 23 January 2017]

Anderson, C. (2012) ‘The History of the Future’ and ‘Epilogue: The New Industrial World’ in Makers: The New Industrial Revolutions, London: Random House, pp 33-52 and 225-230.

Swab, Klaus (2016) ‘Introduction’ to The Fourth Industrial Revolution, World Economic Forum. Available from: https://www.weforum.org/about/the-fourth-industrial-revolution-by-klaus-schwab [Accessed 23 January 2017]

Leave a comment